As we walked, they told me

that they were businessmen, and had been in various Chinese cities over

the past 20 days. I said I taught English at a medical university in

southwest China, and had come to Beijing for a former student’s wedding.

Today (at any moment, actually) I would head to the airport to return to

Kunming. They too were nearing the end of their trip, and really hoped to

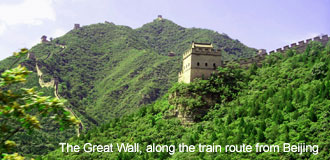

see the Great Wall before going back to Iran.

Down the block, there were

no signs for a tour company or tour bus, so I stepped into a convenience

store to make inquiries. The clerk said she didn’t know anything about a

bus, but there was a travel agent at the other end of the building, so off

we went. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to translate everything I was

saying back into English, which must have been unsettling for the

Iranians, but Hassan radiated a confident, understanding attitude, and

stayed with me as we headed for the other entrance.

In the lobby at the other

end of the building, I was told to try room 201, so Hassan, Ali and I

bounded up the stairs (we had lost the other two at this point; my guess

is that they couldn’t speak English and figured that we would eventually

have to come back the way we came). Upstairs, there were lots of travel

posters in room 201, and a young lady greeted us cordially, but the

posters made it obvious that their specialty was trips abroad, not local

excursions. Nonetheless, the Chinese woman listened to my brief

explanation of our need and offered to help. In the next office, she made

a call or two, and soon reported that there were no more tour bus tickets

or train tickets available today. “Ming tian zenmeyang?”

“How about tomorrow?” I

translated.

“No,” Hassan replied,

“tomorrow we go back to Iran.”

After an awkward moment of

silence, the travel agent suggested that they take a public bus. I'd seen

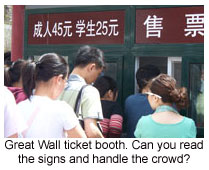

the 191 terminus at Badaling (the nearest and thus most popular section of

the Great Wall), and asked the agent where they could board on the Beijing

end.

As she said “Go to

Deshengmen,” Ali pulled out his subway map. I translated: “Do you know how

to get to the subway?” They nodded. “Take line 10 to line 1, then line 1

to line 2. At Xizhimen get off. Up on the street, ask a traffic policeman

to point you toward Deshengmen. The bus will only cost a few yuan.”

I imagined any number of

problems along the route, but Hassan simply said, “OK, no problem.”

I wasn’t convinced, so I

asked the agent how much it would cost to go to the Badaling section of

the Wall by taxi. Again, she politely made a phone call, and reported back

that it would cost about 230-250 yuan, depending on the traffic. Divided

four ways, this sounded reasonable to the men, so Hassan, through me,

asked if she could call a reputable taxi.

“No,” she replied. “Just

go out on the street and flag one down.”

“But,” I protested in

Chinese, “these men don’t speak Chinese, so I’m afraid that some drivers

will cheat them, or change the fare once they arrive, or take them

someplace they didn’t intend to go. Don’t you know someone trustworthy who

could come pick them up? Who did you just call?”

“Oh, Beijing taxis would

never treat a foreigner like that. You just go outside and find any taxi.”

My mobile phone rang, and

my wife anxiously notified me that our friend had arrived, we were running

late, our suitcase was in the trunk, and they wanted to know where to pick

me up. “Just turn right,” I replied, “and you’ll see me at the end of the

block.”

Outside, I flagged down a

taxi, and said in Chinese: “My friends don’t speak Chinese, but want to go

to the Great Wall. How much would that cost?” The driver asked if they

wanted to go one way or both ways. “Well, give me an estimate for both.”

“About 900 yuan for both

ways,” he replied in Chinese. “About 600 one way.” (So much for 250 yuan!)

Though my friend’s car was

now behind the taxi, I argued for a moment, translating salient parts back

to the Iranians.

“No,” Hassan said, “we

can’t afford 600.”

“Well, how about taking

this taxi to Deshengmen?” I asked. “The driver will use a meter, and drop

you off where you can catch the bus to the Great Wall. It will save you

time over the subway (I hope), and at least you won’t get lost.”

This suggestion was

translated into a language I couldn’t understand for the other three, and

was greeted with great approval. They piled into the taxi, thanking me

profusely for the blur of activity that had just transpired, and

adventurously sped off to make their last day in China a memorable one.

At the same moment I

jumped into another car, and my only regret was that I couldn’t have done

more. It would have been fun to spend the day with them, or to hear about

their adventure over a cup of Chinese tea that evening. But alas, my

flight was waiting.

The oddity of this

Iran-America-China connection didn't really hit me until we drove off in

opposite directions. Up to that moment, I'd been too busy to really care

about who they were or where they were from or what kind of relationship I

was supposed to be having with them. People from three extremely diverse

cultures had interacted, and I was the unlikely link. It occurred to me

that too often we interact with strangers on the basis of prejudice

instead of on any realistic appraisal. I also thought about how much

easier it would be for people to get along if they just tried to work on a

current objective instead of acting in reaction to decades or centuries of

hostility. In most circumstances, these people would have never sought

each other, but thrust together we got along just fine.

Core Values, Divine

Appointments, and Real Neighbors

I’ve traveled to about

twenty countries on five continents, and I’m convinced that it is not the

people of the world who put up the walls that divide us. Most

people are friendly, or are at least cordial, even to strangers. Sure,

there are exceptions, as we saw on September 11 and frequently read about

in the news, but the reason we hear about them is that they are

exceptions. The constant sensational coverage of these exceptions, mixed

with our innate nationalism, create or deepen our international mistrust

and fear. Whatever our motives, Hassan, Ali, myself and the Chinese clerks

had interacted around a common goal. It all happened so fast that it was

almost like an automatic series of events, but surely I would have done

just as much for any human being in similar circumstances. If you

are thinking, “I wouldn’t have,” then I challenge you to examine

your core values—do they promote division in the human family or harmony?

On Tuesday, back in

Kunming, my students reacted with amazement to this story, which is

understandable considering that America and Iran are not exactly

friends. Yet here I was, an American, acting as interpreter and tour

consultant to a car load of Iranians. I told my students that, as a

Christian, I didn't believe meetings like this occur by accident. "I

believe God planned for me to walk out at just that moment,” I said, “so

that I could meet and help these men." Why? That is harder to answer.

Maybe it was simply so that this little group of Iranians, Chinese people

and Americans could see each other in a different light. Hopefully, when

these men think of "America" they will remember the Chinese-speaking guy

who went out of his way to help them. Similarly, when I think of Iran,

maybe I will not initially remember the Iran Hostage Crisis (that clouded

444 days when I was in college) or wonder if someday they will use nuclear

power against their neighbors or against my countrymen; instead, I'll

remember a friendly guy who treated me with respect, who had taken the

time to learn my language, and who allowed me to act like a neighbor, one

day on the streets of Beijing. And maybe, the hotel clerk, travel agent

and taxi driver will also look differently at people from both the US and

Iran. "If these guys could treat each other like friends,” I hope they

will say, “then maybe there is more hope for peace than we’ve been led to

believe, between middle-eastern people and western people."

Centuries ago, in answer

to the question "Who is my neighbor?", a parable was told about a guy beat

up by bandits, laying on the side of the road. Two of his countrymen

passed by without being "neighborly," but then a "foreigner" stopped,

applied first aid, transported him to a safer place, and made arrangements

for the victim's continued care. When Jesus told the story, he didn't end

by asking "Who should you treat like a neighbor?" Instead, he asked:

“Which one of these three men do you think was a neighbor to the man who

was attacked by the robbers?" (Luke 10:36, 37 NCV). After his listener

answered, “The one who showed him mercy,” Jesus said to him, “Then go and

do what he did.”

In other words, our

neighbors aren't necessarily the people who live around us or who think

like us, but the people who need us in the course of our daily lives. That

Samaritan didn't wake up planning to help out someone from a people group

who was prejudiced against his own people, but he had the compassion to

look beyond his prejudices to help someone in need.

The world would be

smaller, safer and more friendly if we all were more willing to “go and do

what he did.”